Los Angeles, CA

The name Emilie Halpern was written a handful of times in my notes from studio visits while getting my MFA from Art Center College of Design. She had graduated a few years before me so we hadn’t met in school, but her name became a familiar one as several different professors mentioned that our work had some cross over and that I should look her up. Even though I didn’t know her, and we worked in very different mediums, our work felt like some kind of art siblings. We finally met years later in 2013 at the opening of her trilogy of shows at Pepin Moore. Turns out she knew who I was too, we formed an instant friendship.

Emilie has a diverse practice ranging from photography and installation based work to ceramics. Her work is a poetic look at natural phenomena and science, distilling big ideas from these fields down to their essence where it becomes personal and intimate. She contemplates life in a way that one can only find inspiring, particularly the way she has lived this last year and a half of her life, experiencing the death of her husband and having breast cancer.

I can’t think of a better person to interview for the first installment of Practice Practice than my dear friend and artist, Emilie Halpern.

Lauren Spencer King - I have been thinking, both in my studio practice and in my meditation practice, about what happens when you continually show up? I thought about how your work gets made. You have two or even three different ways of working. I know some of the work is made in the studio and some is made “in situ” , and hasn’t had a prior life in the studio. Do you feel a difference with these different working methods?

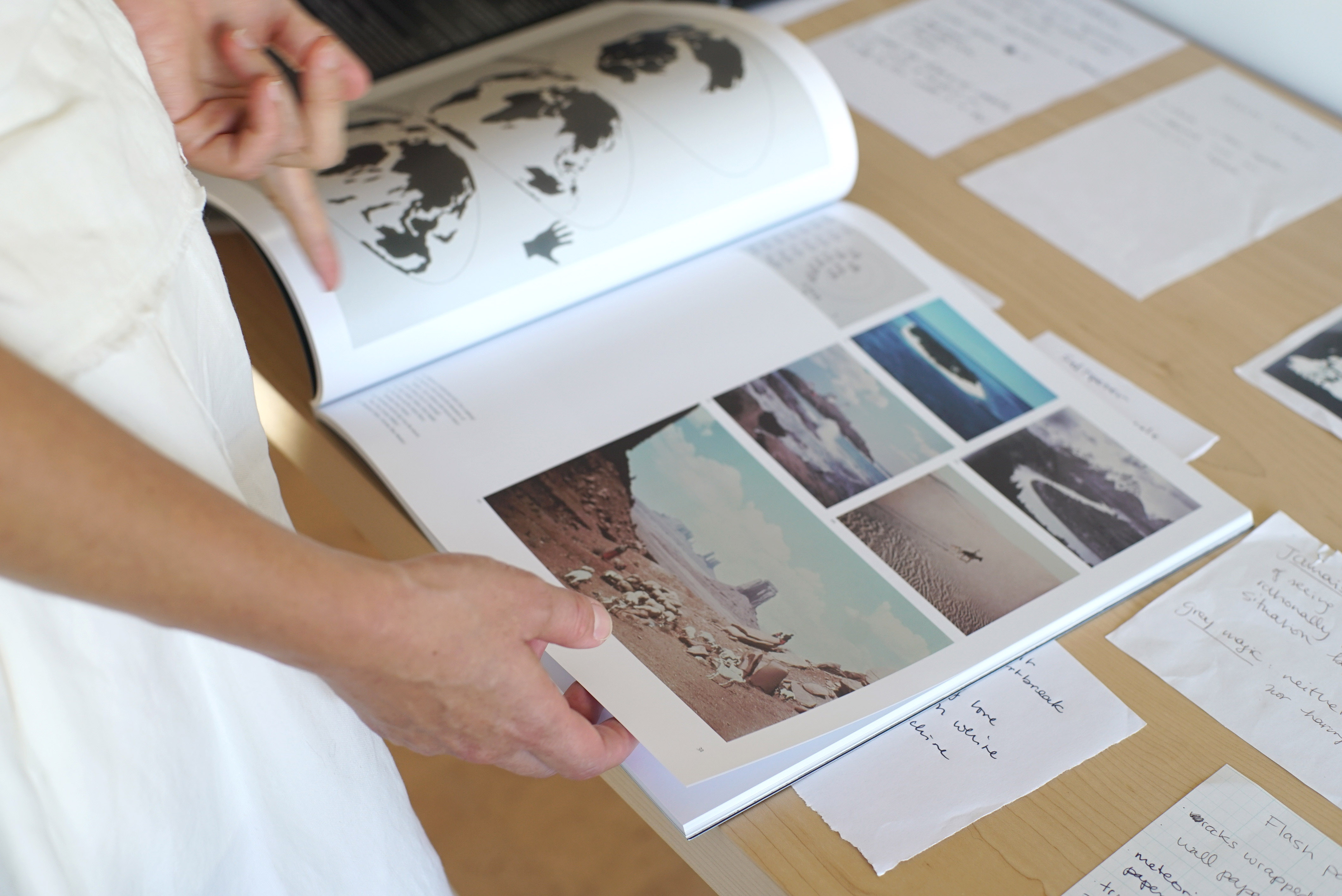

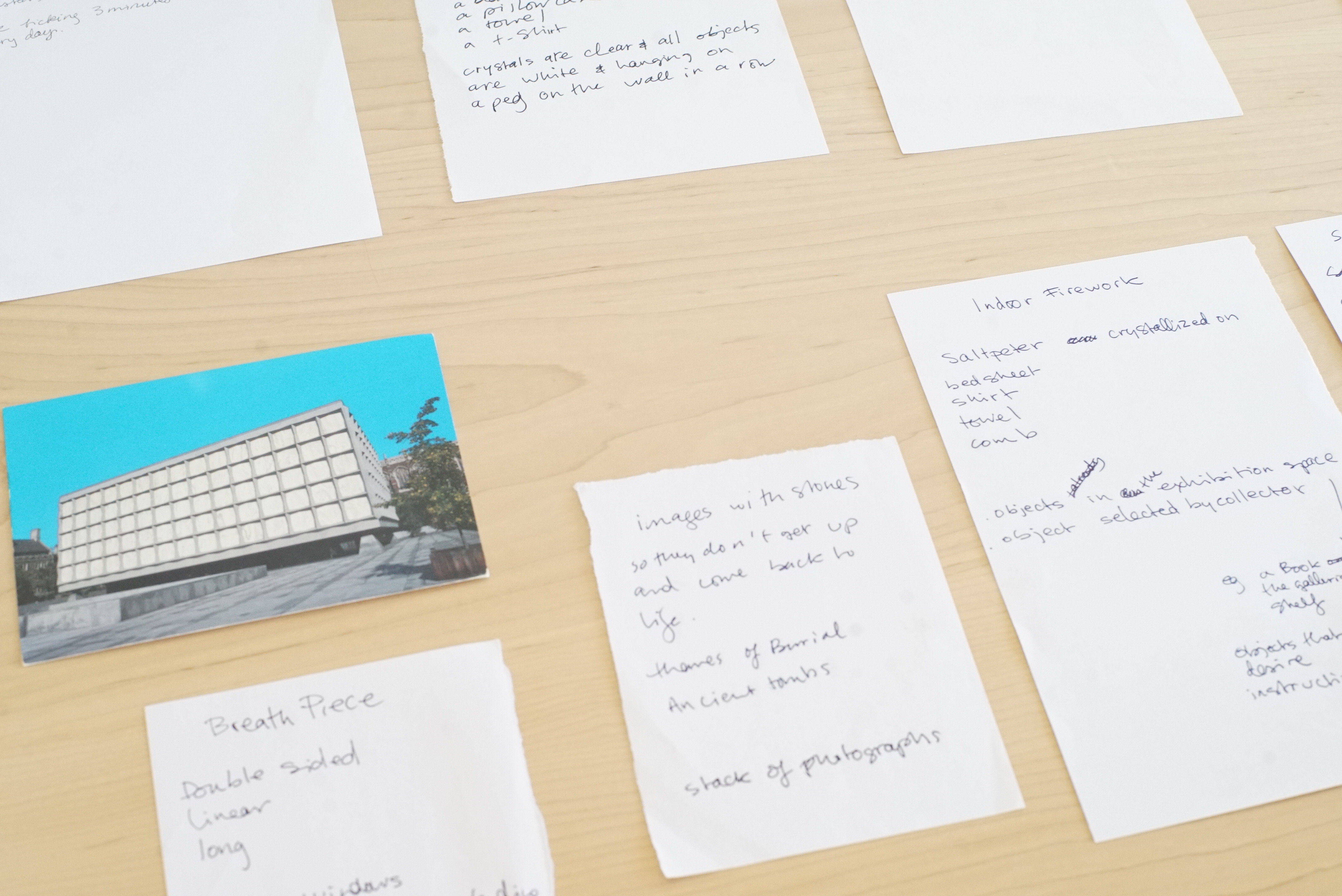

Emilie Halpern - I think the work that’s created in the gallery space, instead of the studio, has a different arc of when I freak out about it. (Laughs) Especially the installation based work, as opposed to my ceramics practice. The practice I started in graduate school, that is more installation based and sculpture based, shifted over time from being made in the studio to being made in the gallery. It starts with just the idea. I love that part because it’s so generative. I spend most of my time distilling it, playing with it, turning it over in my head at any point in my day. I take notes and write things down.

It started was when I was doing a residency in St. Barts ten years ago. I had a paper pad that I found in the house where I was staying. It was the perfect size for writing down one idea on each page. I spent the whole residency generating ideas. I would go into nature, go for a swim, and then come back with all these artworks in my mind. I also had my laptop, so once I would think of something I could do a lot of research on the internet. I would criss-cross doing research and going into nature, having quiet time to think. Then I took the notepad apart and put the pages all over the wall. I really enjoy that part of the practice. With the notes on paper, I was really inspired by Yoko Ono’s book “Grapefruit”. Once I select an idea for a space, then the process shifts to figuring out how to get the materials into the space. That part is really hard for me. I’m not good at getting on the phone and being resourceful. But, somehow that’s always been part of my practice. I don’t enjoy it, so it’s nerve wrecking.

You don’t? I always feel the process of discovery in your work. The story of sourcing materials is very present in the final incarnation of your installations.

I do like having accumulated that knowledge, but, learning something new is always hard for me. Something simple usually gets in my way. Maybe I will get better at it.

I’ve seen your notes on the table. Do you archive them?

It’s a deconstructed sketch book. For me it’s helpful to see the ideas side by side, like a group, not linear. What happens next is editing. It’s similar to photography, which is my background. You have the contact sheet and you circle the one that’s the best. I will edit out an idea, then look at it later and maybe rewrite it or transform it. It’s always exciting to see what stays on the table. I love the ones that haven’t been made but have hung out for so long.

10/09/2018

I read the press release for your current show in Houston. You talked about remaking an old piece and how much the meaning has changed a decade after making it the first time.

Yes. I’ve used different feathers for each exhibition, but it’s the same piece. A scarlet macaw tail feather goes in the wall and sticks out a couple of feet. The one in this show is 26’’ long. It’s very dramatic. I first made it after Travis and I got engaged. The piece is titled “Mate for Life” (macaws mate for life). To make it again was also a change in my practice. A lot of the work I make comes from things I’m experiencing; ideas about how to transfer these romantic emotions, desire or love, into objects. When I first made that piece, my work had been about longing and distance, exploring the suffering that comes out of love and unrequited love. And here I’d found my mate. There’s a myth that when one of a pair of macaws dies, the other one doesn’t want to keep living, so they throw themselves off the highest bough of a tree. When Travis killed himself, that piece was really different.

And with all you went through after Travis died - having cancer and facing your own mortality - you’ve said that that was a time when you were actively choosing life.

To live it is so different than hearing about it in all those songs I love or the art I was making. That created a real crisis for me. How do I continue to make art about these experiences after I’ve lived them and it’s no longer a romantic idea? It’s very traumatic. It’s not poetic when someone kills themself; it’s really tragic and painful.

What was it like making work again after all of that; to have your first show after you’ve been through so much this past year and a half?

I took a big pause because of Travis’s death and my cancer. But even before that there was a two year break, because I’d started teaching at USC and I did’t make anything during that time. Two years just flew by. I had anticipated that once I become a mother, I would have a hard time making work. But something in me was used to the structure of having shows. So even after my son was born, I kept up with the cadence of doing a solo show, having time in-between, and then another solo show, etc... Looking back, I was like, holy smokes! Harold was so young and I whipped out what was epic for me: a trilogy of solo shows. It’s still, to me, the best work I’ve done. Then my gallery, Pepin Moore, closed, and I started teaching which pulled me away from my practice. And then when I turned 40, I started doing a lot of inner work, focusing on family growth. I realized that in order for that growth to happen, I couldn’t be checked out teaching.

Is that when the ceramics started?

It was actually a lot earlier than that. I was hitting a crisis with my practice ten years ago. I’d just had a few solo shows after graduate school. I was selling work, cranking it out, and growing, growing, growing. I started to feel a disconnect from enjoying it. It was work. I was young and looking for outside praise and I was getting lost. When I was an undergraduate at UCLA, I had an opportunity to study ceramics. They had an excellent department headed by Adrian Saxe. I asked Mary Kelly to write a note so I wouldn’t have to do my undergraduate ceramics requirement. Looking back, it’s hilarious because it has become such a big part of what I do now. At the time I was like This is craft. I’m a video artist! I’m an installation artist! This is not at all what I need to explore.

![]()

How did you keep up your studio practice once you were out of graduate school?

When I finished Art Center, I became an art teacher for children. I wanted to keep some kind of structure.

I think that is so smart! Part of staying consistent is having structure. And once you stop it takes even more energy to start again. Do you think you’ve learned how to create structure for yourself?

No. (Laughs) It’s a struggle. Mike Kelly who was my professor --

I forgot you were at Art Center when Mike was there.

Yes. It was a special time. He actually killed himself the day I went into labor with Harold. Now that I have such a different relationship to suicide, it brings back this whole thing about death and life, it’s so big for me. I saw our community trying to reconcile the death of this star who brought a lot of people to Los Angeles that wanted to be in his orbit.

Yes. He helped define what was happening in the L.A. art world.

He’s the reason I went to Art Center. I loved how he combined this like fuck you to the world with being incredibly articulate and intelligent. He was this rebel who was really verbal at the same time. He modeled a practice that was similar to someone going in to work. He had a very large studio and a lot of employees. He showed up 9 to 5 and went to work. And I was like, oh wow, this is what you’re supposed to do. Even in grad school, I had a hard time with that. Thank God for classes and crits because otherwise I would have been at the beach all day looking at tide pools. (Laughs.) I always took the summers off at school, I always wanted to travel.

But, I think that’s important to your practice. What you do in the time away from the studio really informs what is made in here, especially when so much of it connects to ideas from the natural world and science.

Yes. Absolutely. I am kind of making fun of it, but it’s a very important part of how I make my work. When I travel I get inspired; it’s when I can wrap my head around my art. I have so many ideas, and traveling is generative.

When you travel do you get inspired from looking at other art or being in nature?

It’s everything. Seeing art but, also looking at the sea, the sky, the way my body feels in that environment. Just feeling relaxed. The biggest thing is being pulled away from my living environment and all the things that distract me here.

How do you create that space for your practice when you are here? I admire the Mike Kelly discipline, but also know the space away from that is equally valuable.

I think it all comes down to structure. However you can build an external structure, that’s the answer. I think an exhibition creates something to work towards. Part of my practice is more conceptual, it doesn’t necessarily need a studio space. That just exists in my pocket. I’ll be at a stop light, trying to quickly write down an idea. I don’t always want to think about art. It’s stressful. All this doubt can creep into the process that pulls me away from the joy of making it.

![]()

Since we were in the same MFA program, I want to talk about what your life was like after that experience. It’s intense trying to make work while simultaneously trying to understand it and talk about it. Then all of a sudden you’re pushed out into the world to figure it all out.

I remember finding this brochure printed a decade before I was there. It was filled with quotes from the faculty and there was one from Mike Kelly describing the program. He said, “We break you down so you build yourself back up again”. I was totally broken down, having a huge life crisis when I read that. I was like What the fuck? No! Why did no one tell me? It was not easy for my temperament. I’m about positive reinforcement. I’m not about picking something apart so you eventually rebuild yourself.

![]()

I had that feeling too. At the time I resented that method. My mom died after my first term and my work became very personal, so it was hard to be broken down about something I was already so broken about. But when I left, there was something about that rigor that stayed with me. I’m very proud that it’s in my practice and that I demand that of others. It was something I hated at the time, but now it feels like a gift.

One of the other reasons I picked Art Center was that everyone knew that UCLA was product driven. You were going to make something that looked great in the gallery. And at Art Center you might not make shit because you’re gonna be so freaked out, but that’s ok because you’re going to learn a lot about how to verbalize your ideas, write about them, and have the references for why you’re making what you’re making.

I liked how you said how it made you expect that of other artists. It really made me look at my peers work or my teachers work or now, what’s in a gallery. I still have an emotional and intuitive reaction when I love someone’s work, but I can be critical too. When I love someone’s work I can break it down and understand what I love about it, instead of giving up on what I do that intersects with it, I make something that takes it further. I think that is Art Center.

What has your studio practice taught you about the kind of person you are?

It’s interesting: I’m old enough to know who I am, and to really admire my practice, and know that it’s ok that I do it this way. But that’s still something I need to work on. I even saw it just now when I was talking about taking time away from school, and I was making fun of myself. But that’s a huge part of my practice. I need to embrace that cadence and remember that every artist has a different way of approaching this. There isn’t one work ethic that’s better than another. But it’s hard to let that go.

Pleasure is a big part of how I make work. In this anglo saxon protestant culture we don’t think about pleasure driving how we live our lives. I don’t enjoy walking around with the shame of thinking, I should be doing something that I’m not. The best work comes out of finding joy and pleasure in the way I lead my life. I remember getting into a discussion with Anna Helwing, my first gallerist, who had this traditional idea that suffering artists make the best work; that if you’re in pain, you are your most creative. For a moment I went along but then I realized, Oh hell no! I make the best work when I have the most structure, the most emotional stability, and the most balance in my life. And a lot of that comes from being away from making something, not even thinking about it, and just living life.

Thank you Emilie!

![]()

emiliehalpern.com

@emiliehalpern

Yes. I’ve used different feathers for each exhibition, but it’s the same piece. A scarlet macaw tail feather goes in the wall and sticks out a couple of feet. The one in this show is 26’’ long. It’s very dramatic. I first made it after Travis and I got engaged. The piece is titled “Mate for Life” (macaws mate for life). To make it again was also a change in my practice. A lot of the work I make comes from things I’m experiencing; ideas about how to transfer these romantic emotions, desire or love, into objects. When I first made that piece, my work had been about longing and distance, exploring the suffering that comes out of love and unrequited love. And here I’d found my mate. There’s a myth that when one of a pair of macaws dies, the other one doesn’t want to keep living, so they throw themselves off the highest bough of a tree. When Travis killed himself, that piece was really different.

And with all you went through after Travis died - having cancer and facing your own mortality - you’ve said that that was a time when you were actively choosing life.

To live it is so different than hearing about it in all those songs I love or the art I was making. That created a real crisis for me. How do I continue to make art about these experiences after I’ve lived them and it’s no longer a romantic idea? It’s very traumatic. It’s not poetic when someone kills themself; it’s really tragic and painful.

What was it like making work again after all of that; to have your first show after you’ve been through so much this past year and a half?

I took a big pause because of Travis’s death and my cancer. But even before that there was a two year break, because I’d started teaching at USC and I did’t make anything during that time. Two years just flew by. I had anticipated that once I become a mother, I would have a hard time making work. But something in me was used to the structure of having shows. So even after my son was born, I kept up with the cadence of doing a solo show, having time in-between, and then another solo show, etc... Looking back, I was like, holy smokes! Harold was so young and I whipped out what was epic for me: a trilogy of solo shows. It’s still, to me, the best work I’ve done. Then my gallery, Pepin Moore, closed, and I started teaching which pulled me away from my practice. And then when I turned 40, I started doing a lot of inner work, focusing on family growth. I realized that in order for that growth to happen, I couldn’t be checked out teaching.

Is that when the ceramics started?

It was actually a lot earlier than that. I was hitting a crisis with my practice ten years ago. I’d just had a few solo shows after graduate school. I was selling work, cranking it out, and growing, growing, growing. I started to feel a disconnect from enjoying it. It was work. I was young and looking for outside praise and I was getting lost. When I was an undergraduate at UCLA, I had an opportunity to study ceramics. They had an excellent department headed by Adrian Saxe. I asked Mary Kelly to write a note so I wouldn’t have to do my undergraduate ceramics requirement. Looking back, it’s hilarious because it has become such a big part of what I do now. At the time I was like This is craft. I’m a video artist! I’m an installation artist! This is not at all what I need to explore.

When I finished Art Center, I became an art teacher for children. I wanted to keep some kind of structure.

I think that is so smart! Part of staying consistent is having structure. And once you stop it takes even more energy to start again. Do you think you’ve learned how to create structure for yourself?

No. (Laughs) It’s a struggle. Mike Kelly who was my professor --

I forgot you were at Art Center when Mike was there.

Yes. It was a special time. He actually killed himself the day I went into labor with Harold. Now that I have such a different relationship to suicide, it brings back this whole thing about death and life, it’s so big for me. I saw our community trying to reconcile the death of this star who brought a lot of people to Los Angeles that wanted to be in his orbit.

Yes. He helped define what was happening in the L.A. art world.

He’s the reason I went to Art Center. I loved how he combined this like fuck you to the world with being incredibly articulate and intelligent. He was this rebel who was really verbal at the same time. He modeled a practice that was similar to someone going in to work. He had a very large studio and a lot of employees. He showed up 9 to 5 and went to work. And I was like, oh wow, this is what you’re supposed to do. Even in grad school, I had a hard time with that. Thank God for classes and crits because otherwise I would have been at the beach all day looking at tide pools. (Laughs.) I always took the summers off at school, I always wanted to travel.

But, I think that’s important to your practice. What you do in the time away from the studio really informs what is made in here, especially when so much of it connects to ideas from the natural world and science.

Yes. Absolutely. I am kind of making fun of it, but it’s a very important part of how I make my work. When I travel I get inspired; it’s when I can wrap my head around my art. I have so many ideas, and traveling is generative.

When you travel do you get inspired from looking at other art or being in nature?

It’s everything. Seeing art but, also looking at the sea, the sky, the way my body feels in that environment. Just feeling relaxed. The biggest thing is being pulled away from my living environment and all the things that distract me here.

How do you create that space for your practice when you are here? I admire the Mike Kelly discipline, but also know the space away from that is equally valuable.

I think it all comes down to structure. However you can build an external structure, that’s the answer. I think an exhibition creates something to work towards. Part of my practice is more conceptual, it doesn’t necessarily need a studio space. That just exists in my pocket. I’ll be at a stop light, trying to quickly write down an idea. I don’t always want to think about art. It’s stressful. All this doubt can creep into the process that pulls me away from the joy of making it.

Since we were in the same MFA program, I want to talk about what your life was like after that experience. It’s intense trying to make work while simultaneously trying to understand it and talk about it. Then all of a sudden you’re pushed out into the world to figure it all out.

I remember finding this brochure printed a decade before I was there. It was filled with quotes from the faculty and there was one from Mike Kelly describing the program. He said, “We break you down so you build yourself back up again”. I was totally broken down, having a huge life crisis when I read that. I was like What the fuck? No! Why did no one tell me? It was not easy for my temperament. I’m about positive reinforcement. I’m not about picking something apart so you eventually rebuild yourself.

I had that feeling too. At the time I resented that method. My mom died after my first term and my work became very personal, so it was hard to be broken down about something I was already so broken about. But when I left, there was something about that rigor that stayed with me. I’m very proud that it’s in my practice and that I demand that of others. It was something I hated at the time, but now it feels like a gift.

One of the other reasons I picked Art Center was that everyone knew that UCLA was product driven. You were going to make something that looked great in the gallery. And at Art Center you might not make shit because you’re gonna be so freaked out, but that’s ok because you’re going to learn a lot about how to verbalize your ideas, write about them, and have the references for why you’re making what you’re making.

I liked how you said how it made you expect that of other artists. It really made me look at my peers work or my teachers work or now, what’s in a gallery. I still have an emotional and intuitive reaction when I love someone’s work, but I can be critical too. When I love someone’s work I can break it down and understand what I love about it, instead of giving up on what I do that intersects with it, I make something that takes it further. I think that is Art Center.

What has your studio practice taught you about the kind of person you are?

It’s interesting: I’m old enough to know who I am, and to really admire my practice, and know that it’s ok that I do it this way. But that’s still something I need to work on. I even saw it just now when I was talking about taking time away from school, and I was making fun of myself. But that’s a huge part of my practice. I need to embrace that cadence and remember that every artist has a different way of approaching this. There isn’t one work ethic that’s better than another. But it’s hard to let that go.

Pleasure is a big part of how I make work. In this anglo saxon protestant culture we don’t think about pleasure driving how we live our lives. I don’t enjoy walking around with the shame of thinking, I should be doing something that I’m not. The best work comes out of finding joy and pleasure in the way I lead my life. I remember getting into a discussion with Anna Helwing, my first gallerist, who had this traditional idea that suffering artists make the best work; that if you’re in pain, you are your most creative. For a moment I went along but then I realized, Oh hell no! I make the best work when I have the most structure, the most emotional stability, and the most balance in my life. And a lot of that comes from being away from making something, not even thinking about it, and just living life.

Thank you Emilie!

emiliehalpern.com

@emiliehalpern